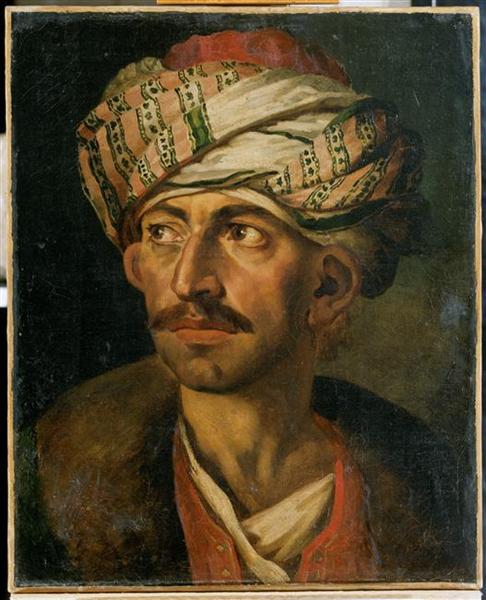

Head of an Oriental man (Portrait of Mustapha)

Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'archéologie de Besançon, Besançon, France

Theodore Gericault, 1820

The Orient—including present-day Turkey, Greece, the Middle East, and North Africa—exerted its allure on the Western artist’s imagination centuries prior to the turn of the nineteenth century. Figures in Middle Eastern dress appear in Renaissance and Baroque works, and the opulent eroticism of harem scenes appealed to the French Rococo aesthetic. Until this point, however, Europeans had minimal contact with the East, usually through trade and intermittent military campaigns. In 1798, a French army led by General Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt and occupied the country until 1801. The European presence in Egypt attracted Western travelers to the Near and Middle East and enhanced connection between two worlds.Throughout his career, Géricault created many fine portraits. The subject of Head of an Oriental man was a real man, a domestic servant of Géricault, a Tunisian Arab named Mustafa Sussen. Apparently, he was a survivor of a shipwreck. Géricault had found him in a Paris street and brought home as a model and companion. It is probably his features, dark eyes sad beneath his turban, that are depicted in several late studies of a Turk that strike the viewer as warmly individualized portraits. Mustafa posed as a model for other painters like Anne-Louis Girodet (Mustapha, 1819) or Horace Vernet (A Man in Oriental Costume, 1818). A vital aspect of the Romantic movement was the full embrace of exotic "oriental" themes in art. Like many artists of the period, Géricault was interested in the world beyond Western Europe. The artist desired to visit the Holy Land so that he could experience the Middle East in all its sounds, sights, and interactions. However, he never managed to travel there and therefore relied on books he read, works with related subjects he collected, and most importantly, his servant Mustapha. Géricault led the way for Orientalist artists such as Eugène Delacroix, Léon Cognet, and Eugène Fromentin, whose travels in Northern Africa formed an essential part of their inspiration.